This article is authored by and courtesy of Michael Shellenberger, who originally published it at his Substack. Along with Shellenberger, Discovery Institute is a lead organizer of North America Recovers, the national coalition mentioned at the end of this article.

Click here to subscribe to Michael Shellenberger’s Substack.

The US Supreme Court recently heard oral arguments about what cities can and cannot do to end homelessness.

What if there is a bed available in the Gospel Rescue Mission, but Ms. Johnson, a person, doesn’t want it? Doesn’t wish to leave their pet. Her Rottweiler’s not permitted there. So that is a difficult question for a person, and a difficult policy question.

What everyone agreed on was that homelessness is a difficult problem.

Many people have mentioned this is a serious policy problem… So, the policy questions in this case are very difficult….Martin speaks in terms of someone who is involuntarily homeless and that raises all of those policy questions… We usually think about whether state law, local law already achieves those purposes so that the federal courts aren’t micromanaging homeless policy…

I think most people listening to the Supreme Court would agree: it isn’t going to solve homelessness. That is a job for state legislators. So why haven’t they? Why has homelessness gotten worse?

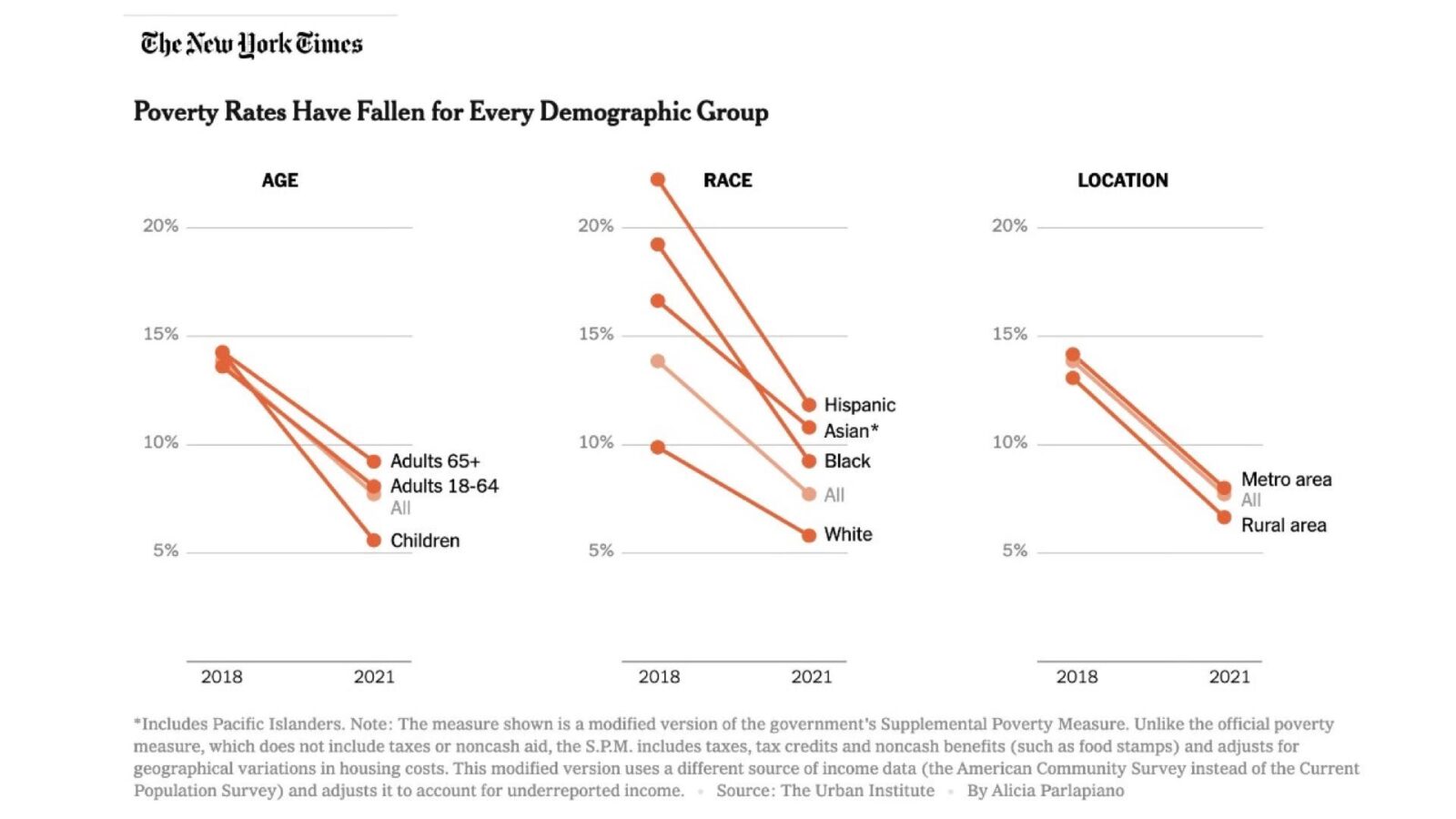

The answer that many homeless advocates give is that it’s because we don’t have enough homes, and poverty has increased. But neither is true. Poverty has steadily declined since the 1980s, when homelessness first became an issue of public concern.

And very few people are on the street simply because they can’t afford the rent.

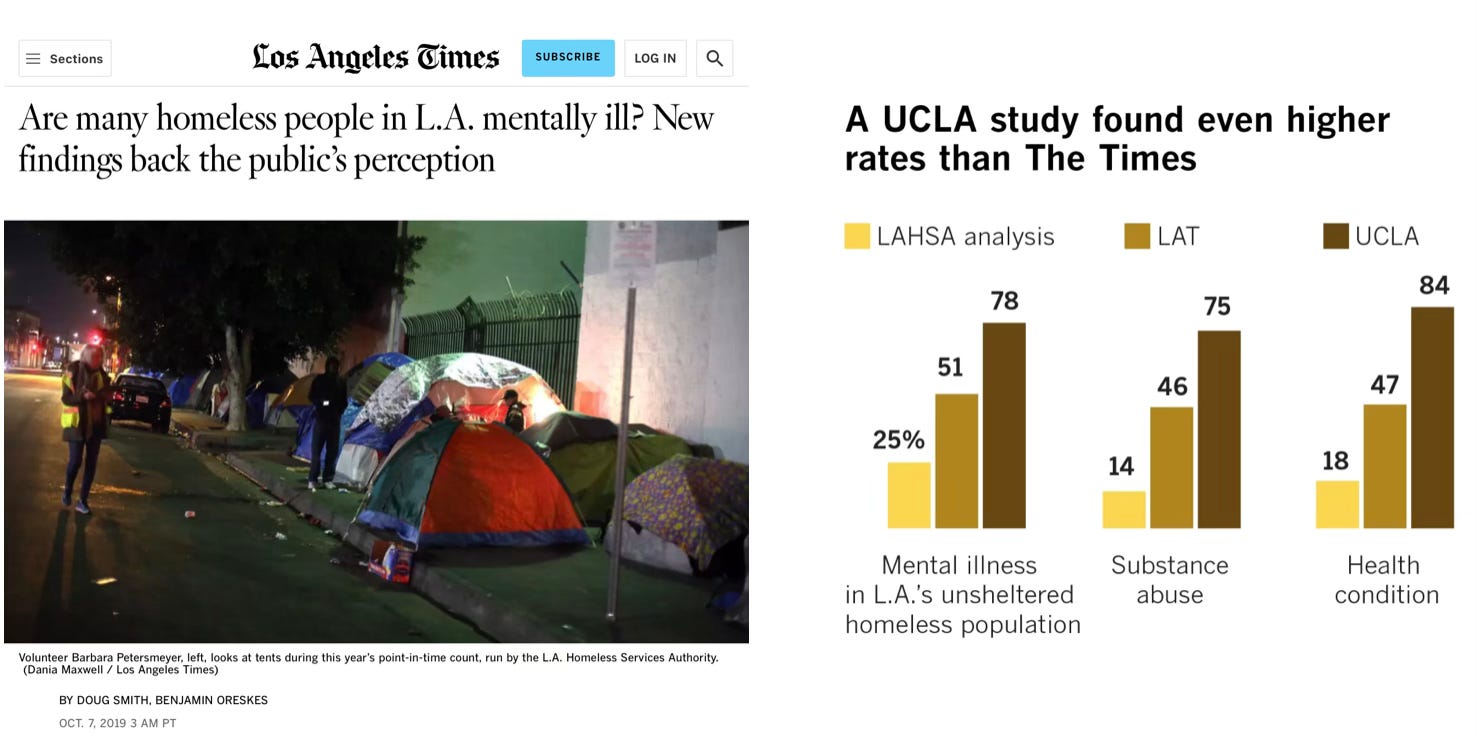

The evidence is overwhelming that the majority of people on the street are there because of untreated mental illness or addiction, which leads people to use all their money to support their drug habit and be high, rather than work.

People who can’t afford the rent but are able to work and aren’t in the grip of addiction or untreated mental illness find a cheaper place to live, move somewhere cheaper, or live with family and friends.

It’s true there aren’t enough shelter beds, case workers, group homes, and psychiatric hospitals to care for the homeless.

But a big part of the reason for that is that advocates for the homeless have, for 40 years, demanded that funding for dealing with the homeless go into giving people private studio apartments rather than building sufficient shelter beds.

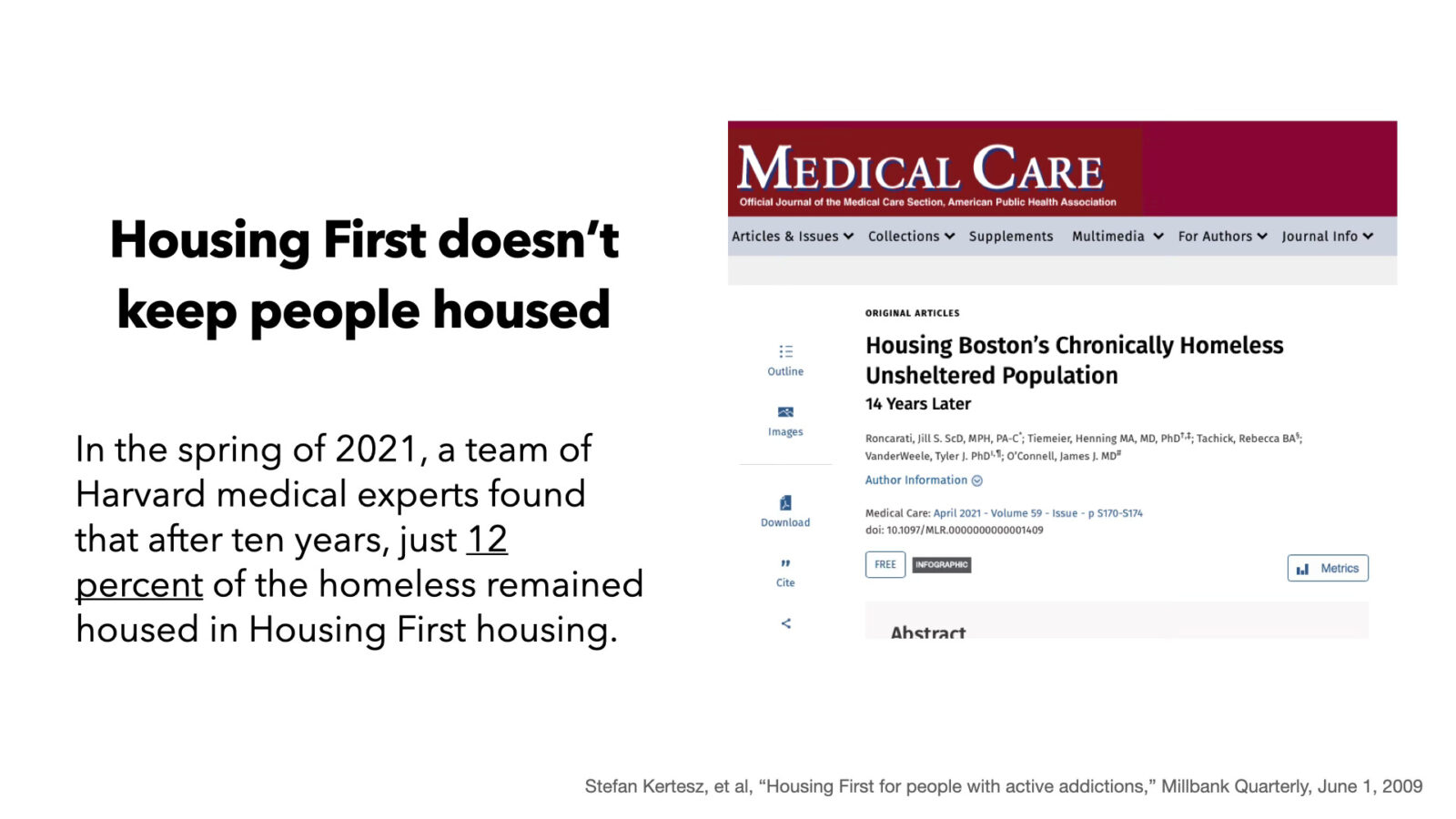

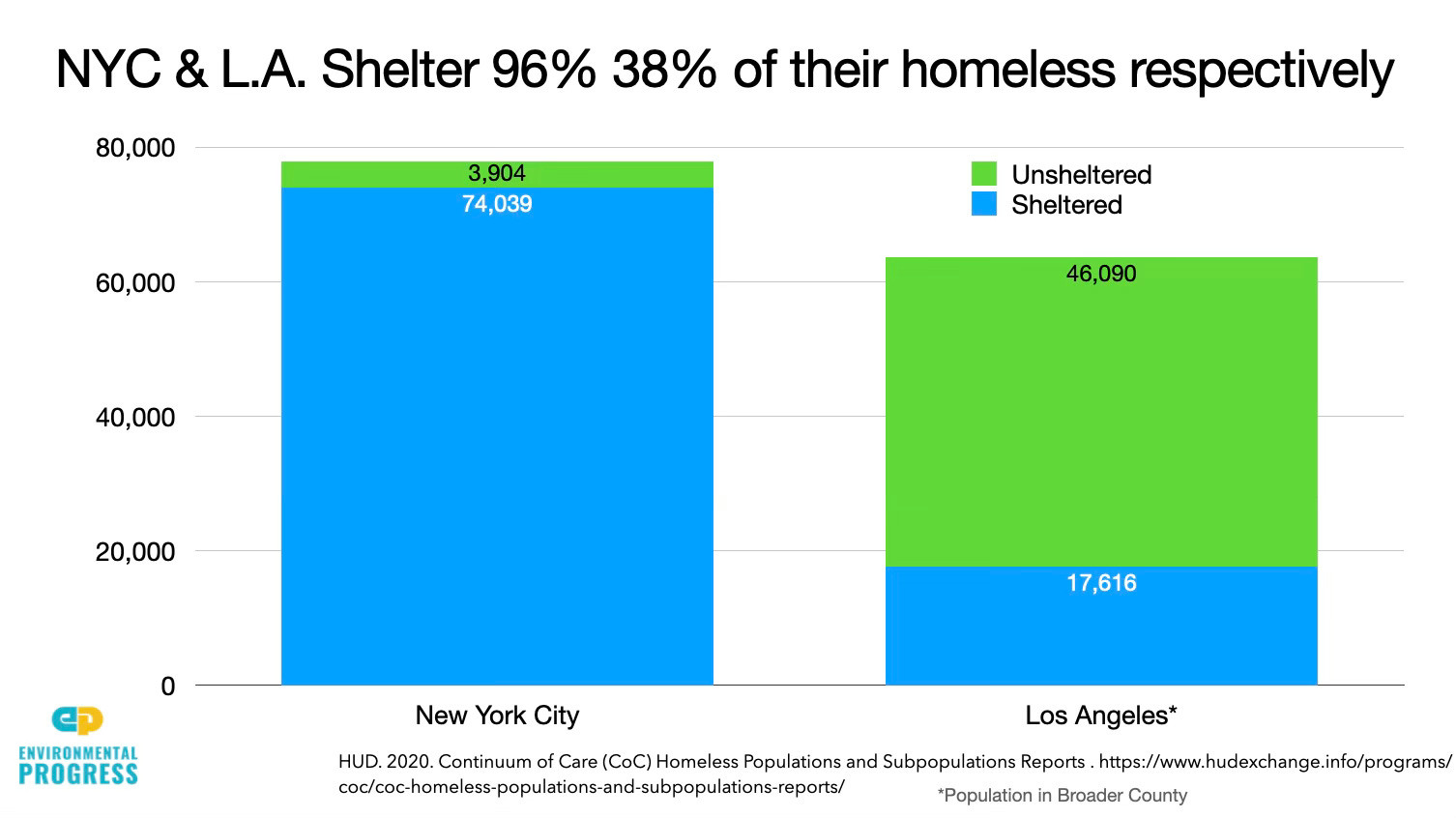

They call this “Housing First,” and its record is awful. Few stay in housing, and many die because it fails to treat the cause of the problem, addiction, and untreated mental illness, rather than the symptoms.

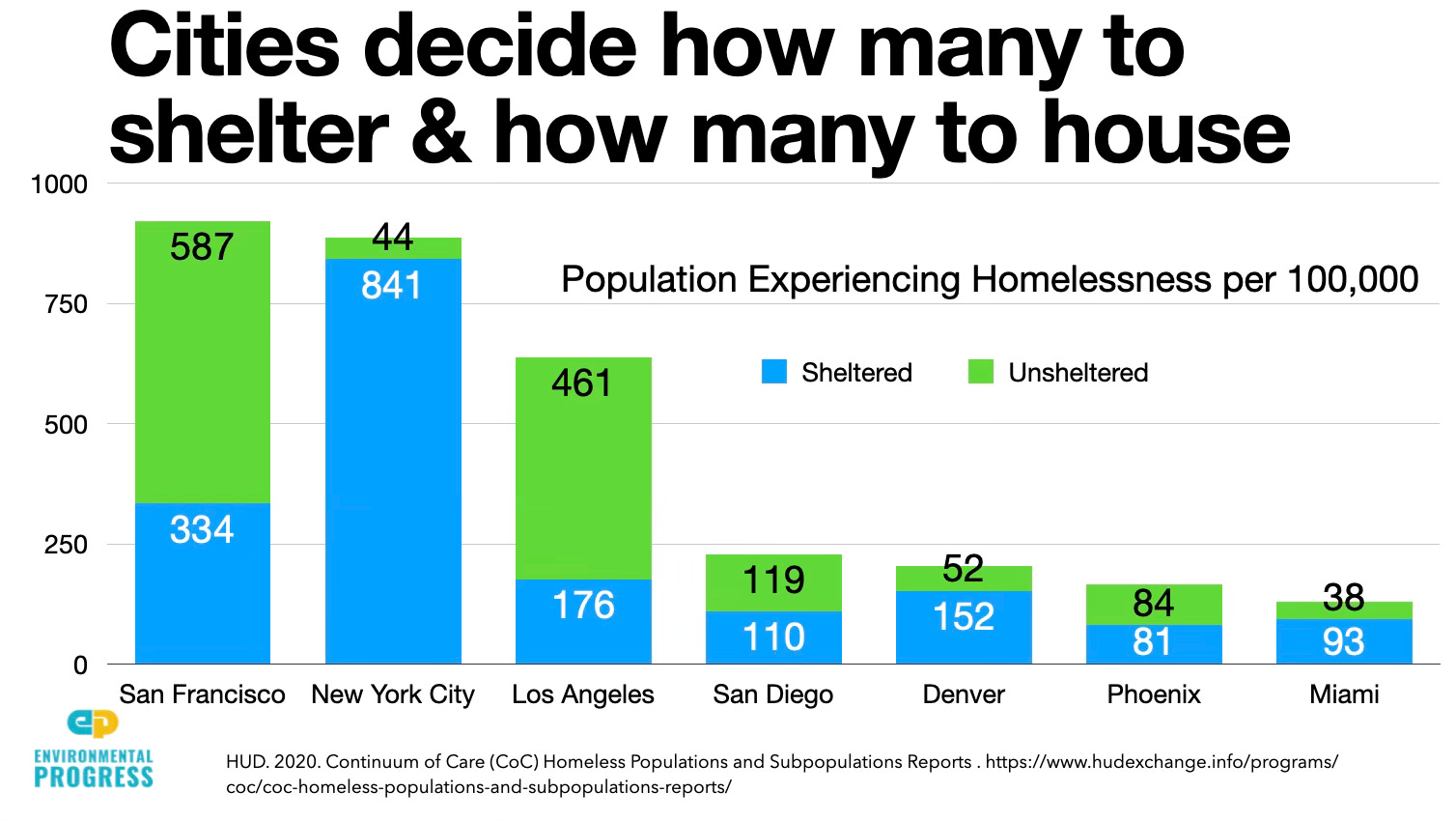

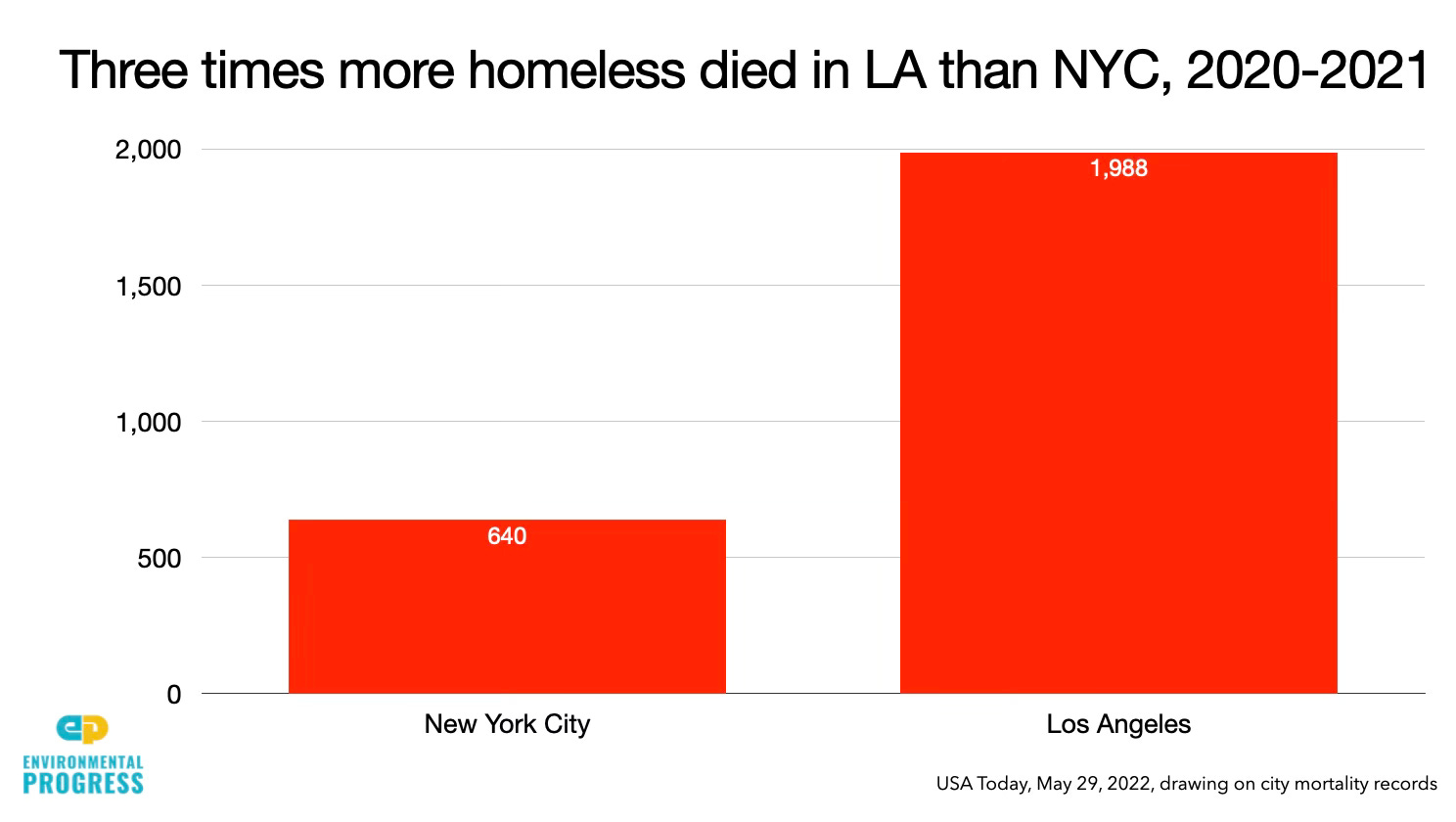

Studies find that cities that prioritize basic shelter over expensive housing reduce the deaths of homeless by 3-fold. And so in LA, homeless die at a rate 3 times higher than New York because living inside protects people from murder, drug overdose, and car accidents.

Making matters worse, homeless advocates, along with the ACLU, have opposed expanding psychiatric hospitals, and mandatory care in general, because they believe it’s worse to mandate hospitalization for people who are dangerously psychotic or manic than to simply leave them on the street.

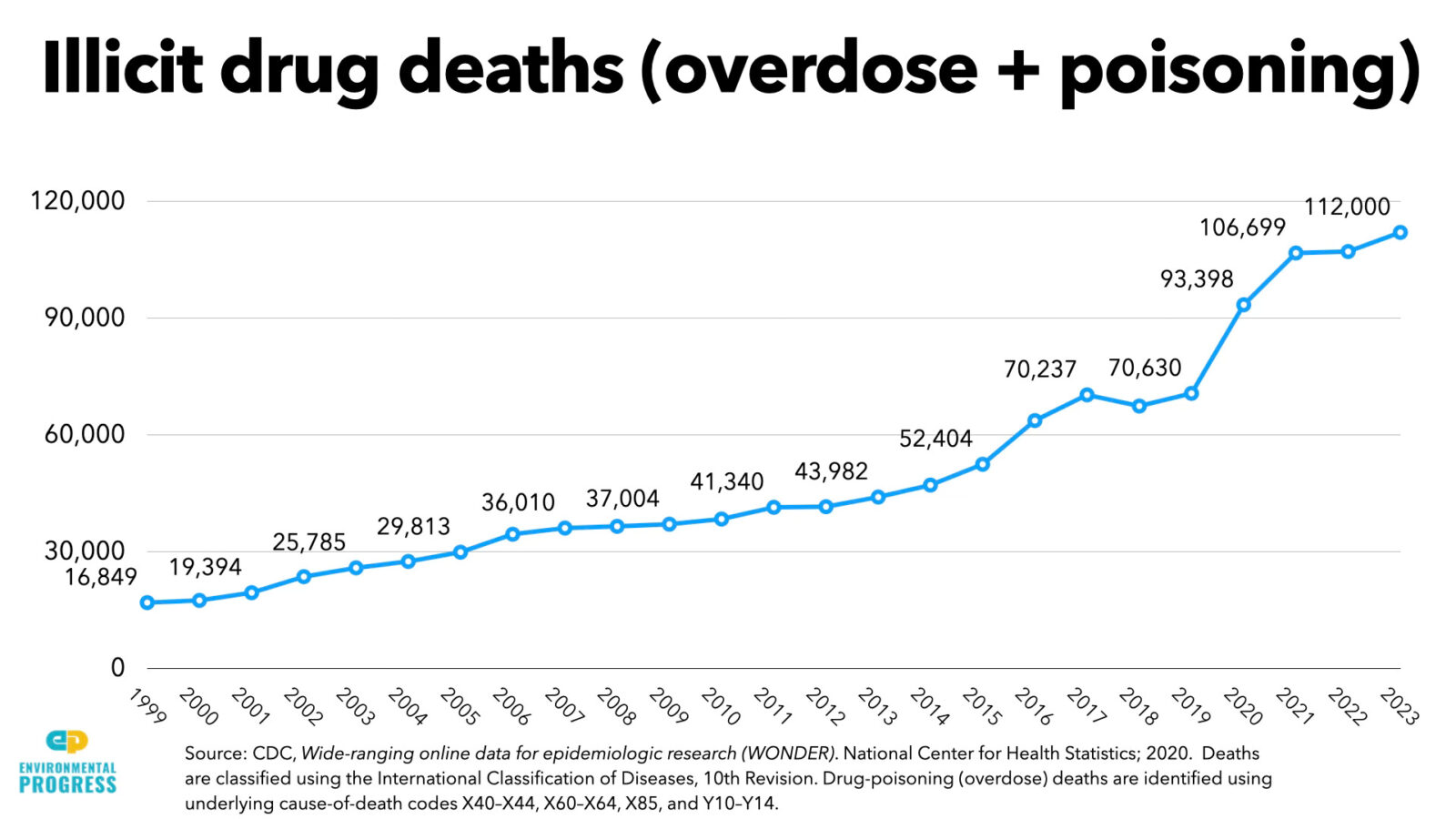

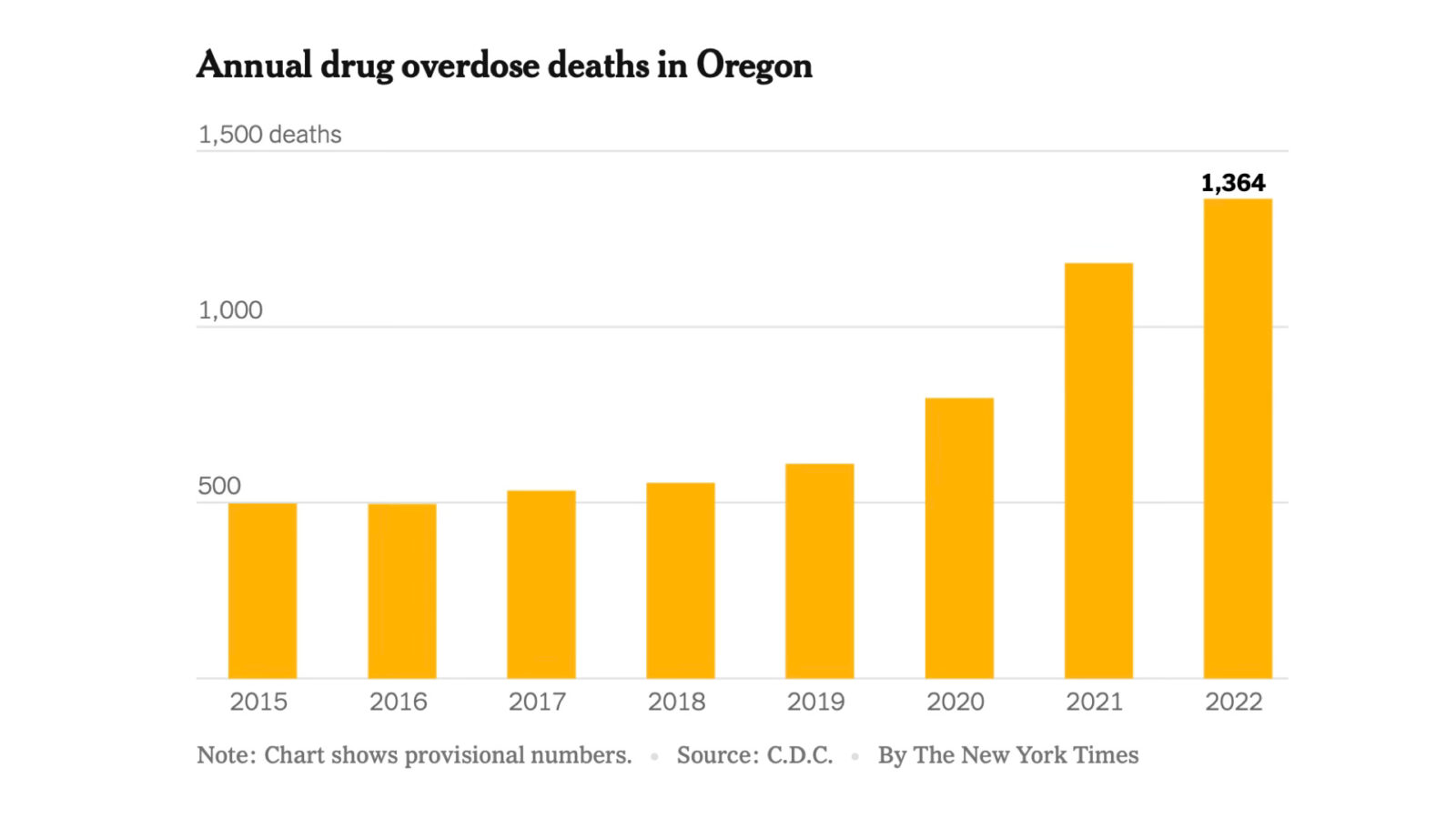

But it’s not. Last year, 112,000 Americans died from drug overdose and poisoning because we failed to mandate treatment. Two of my friends from high school would still be alive today had we mandated they get treatment for addiction rather than letting them die.

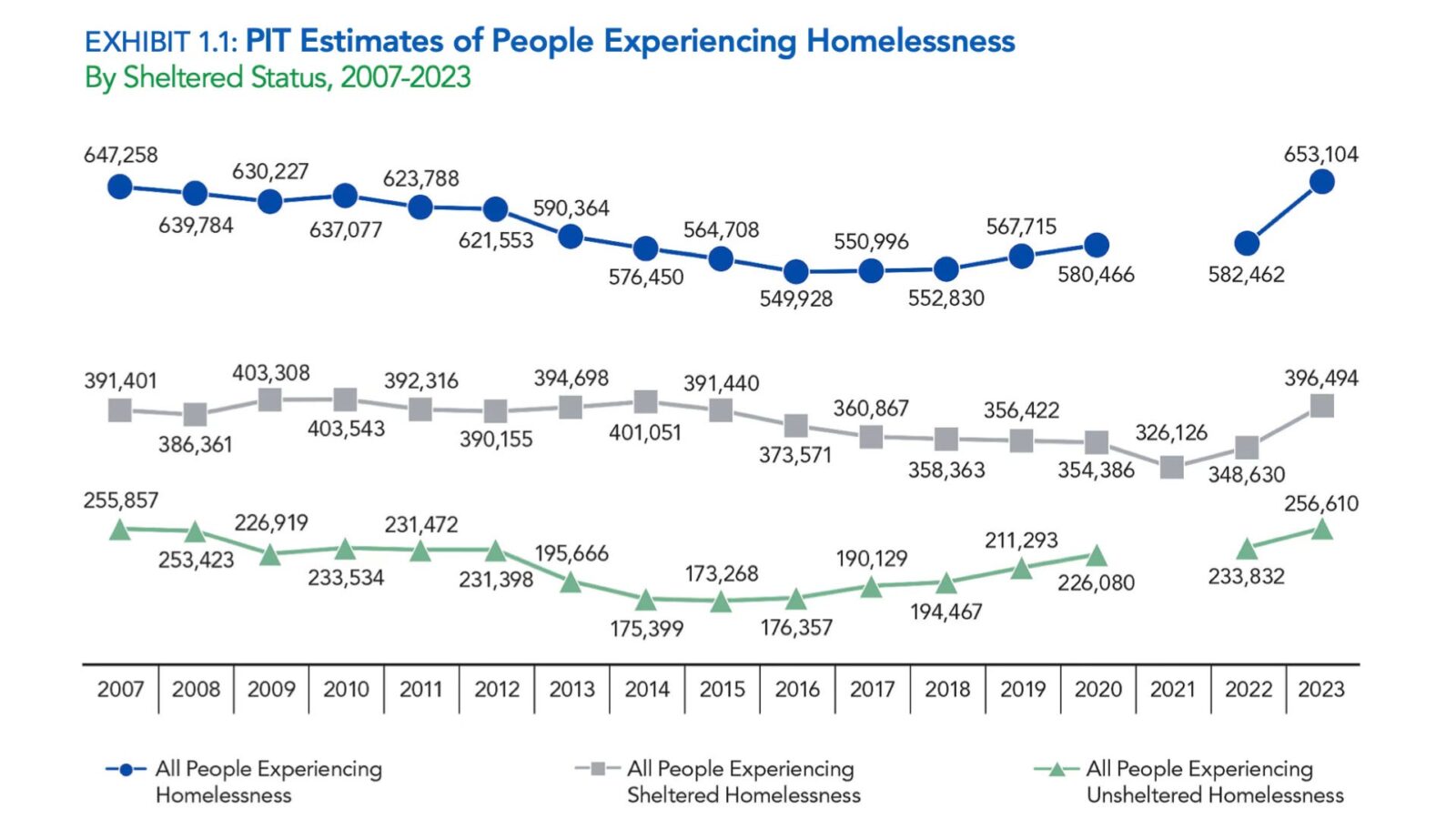

What is happening on homelessness is a record of failure. The number of drug deaths quintupled from 20,000 in 2022 to 112,000 last year.

That’s more people dying per year than died in Hiroshima.

Homelessness is not a fundamental problem of housing. It’s a problem of enabling addiction and untreated mental illness, both of which lead people to give up on work, lie, steal, cheat their families and friends, and live on the street, where they turn to petty crime to sustain their drug habits.

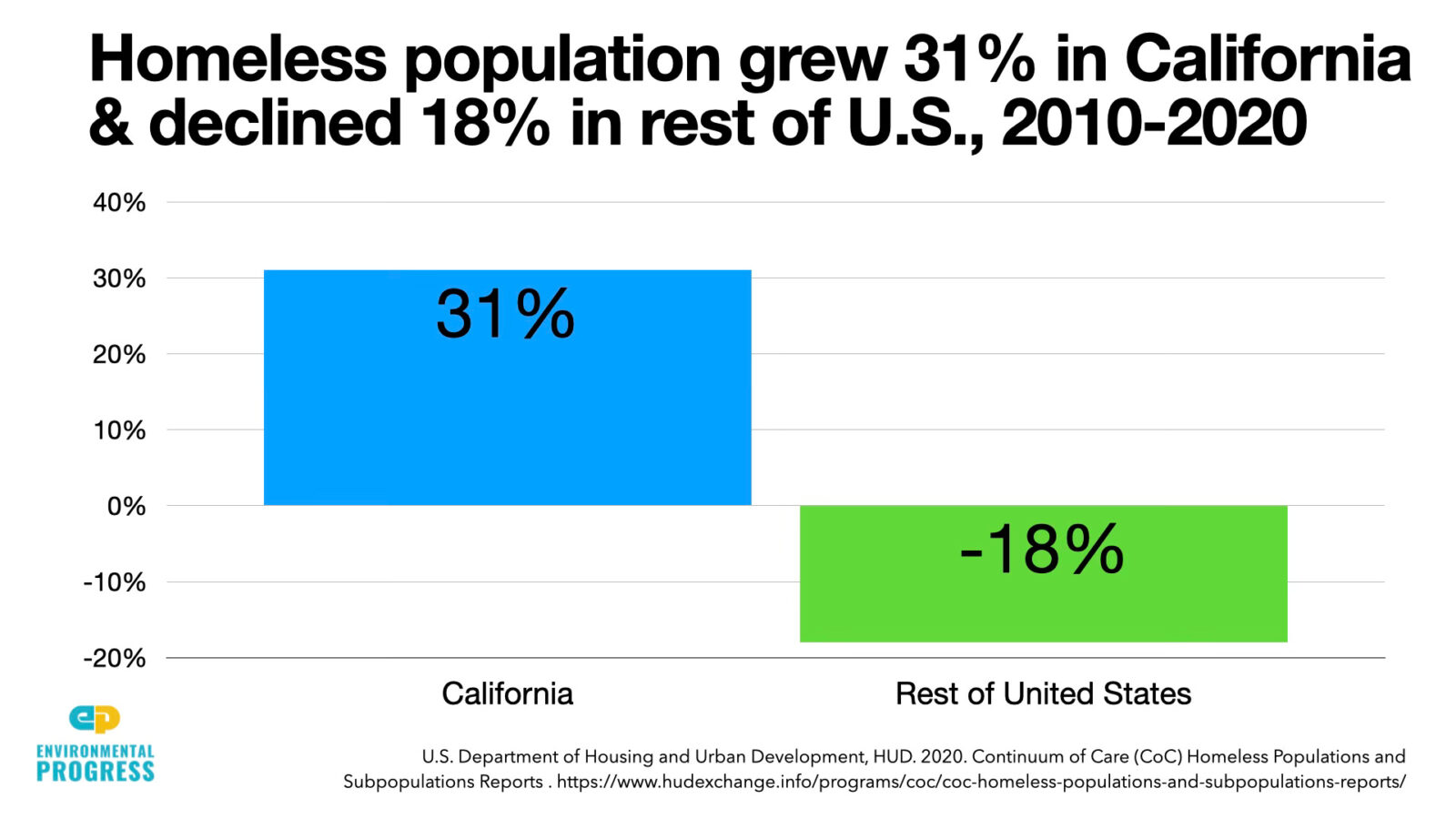

This seems cruel to many people, which is why homelessness has gotten worse. In other words, the reason homelessness has gotten worse is because we’ve enabled it, and subsidized it, rather than funded treatment and recovery. Nobody has subsidized homelessness more than California, Washington, and Oregon. And it’s been in those states that homelessness has worsened the most.

Why? The homelessness groups really believe it’s more cruel to mandate care than to let people die on the streets.

But there is an ideology behind this, too. It’s the idea that people suffering from addiction and mental illness are victims of society or the system, which is fundamentally evil. And, according to their logic, to restore justice in the world, we must give victims whatever they want, including the right to camp anywhere and use hard drugs, even if it results in their death.

You might call this pathological altruism. Think of the Kathy Bates character in Misery.

Or the mother who poisons her child in order to have a sick person to take care of, like in “Sixth Sense.”

It’s no coincidence that the same people who believe this also think civilization is evil and should be replaced by something more akin to primitive anarchism, like the kind romanticized by intellectuals since Rousseau.

The alternative to this dystopia is tough love. We need to give people the care they need, but that’s not through enabling addiction and illegal behavior, but rather enforcing laws and mandating care, as an alternative to jail, when they are broken.

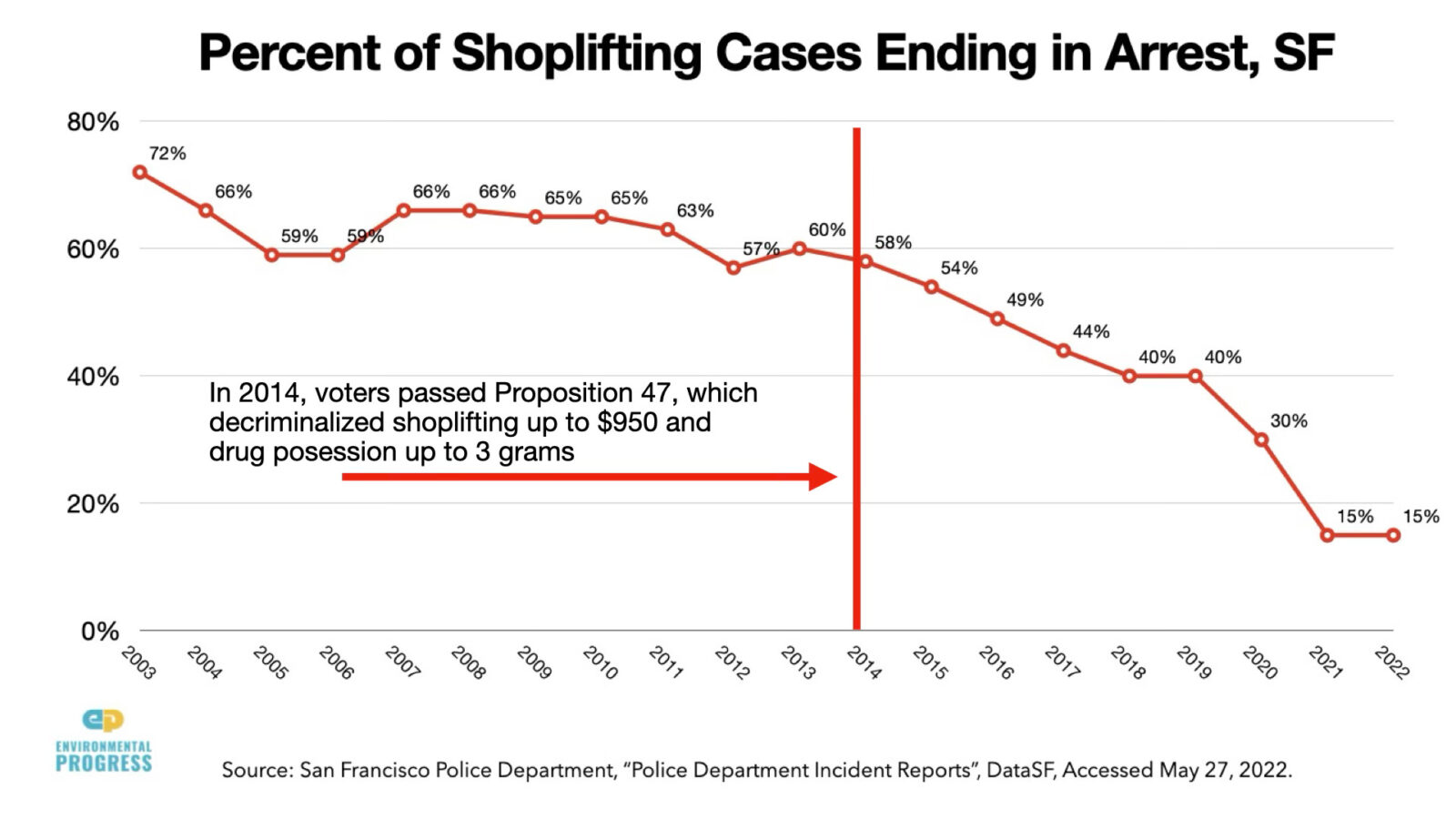

It’s not enough to do what many Republicans want to do, which is to enforce laws and recriminalize shoplifting and hard drugs simply. We need to do that, for sure.

But states must also have caseworkers, group homes, and psychiatric hospitals so there is an alternative to jail, and so states can provide people with the specialized care where it’s available, which simply isn’t going to be in many of the small towns, like the one at the center of the Supreme Court hearing.

The dirty little secret about homelessness, which is also the key to ending it, is that we must both mandate psychiatric and addiction care as an alternative to jail and create a proper statewide psychiatric and addiction care system.

Both things must happen, or we will never solve this problem.

California and other states have many of the tools needed to do this. We have built a statewide and national coalition to demand this. We need a governor who can combine these tools under a single statewide agency, Cal-Psych, with the power to get people off the street and get the care they need.

And we need to pass a ballot initiative to re-criminalize shoplifting and hard drug possession so homeless addicts can get the help they need.

The Supreme Court will make a ruling in June. It won’t make any difference. It’s up to the states to take action and in a way that transcends the agendas of both Democrats and Republicans.

Click here to view this article on Michael Shellenberger’s Substack.