Journey of a Troubled Soul

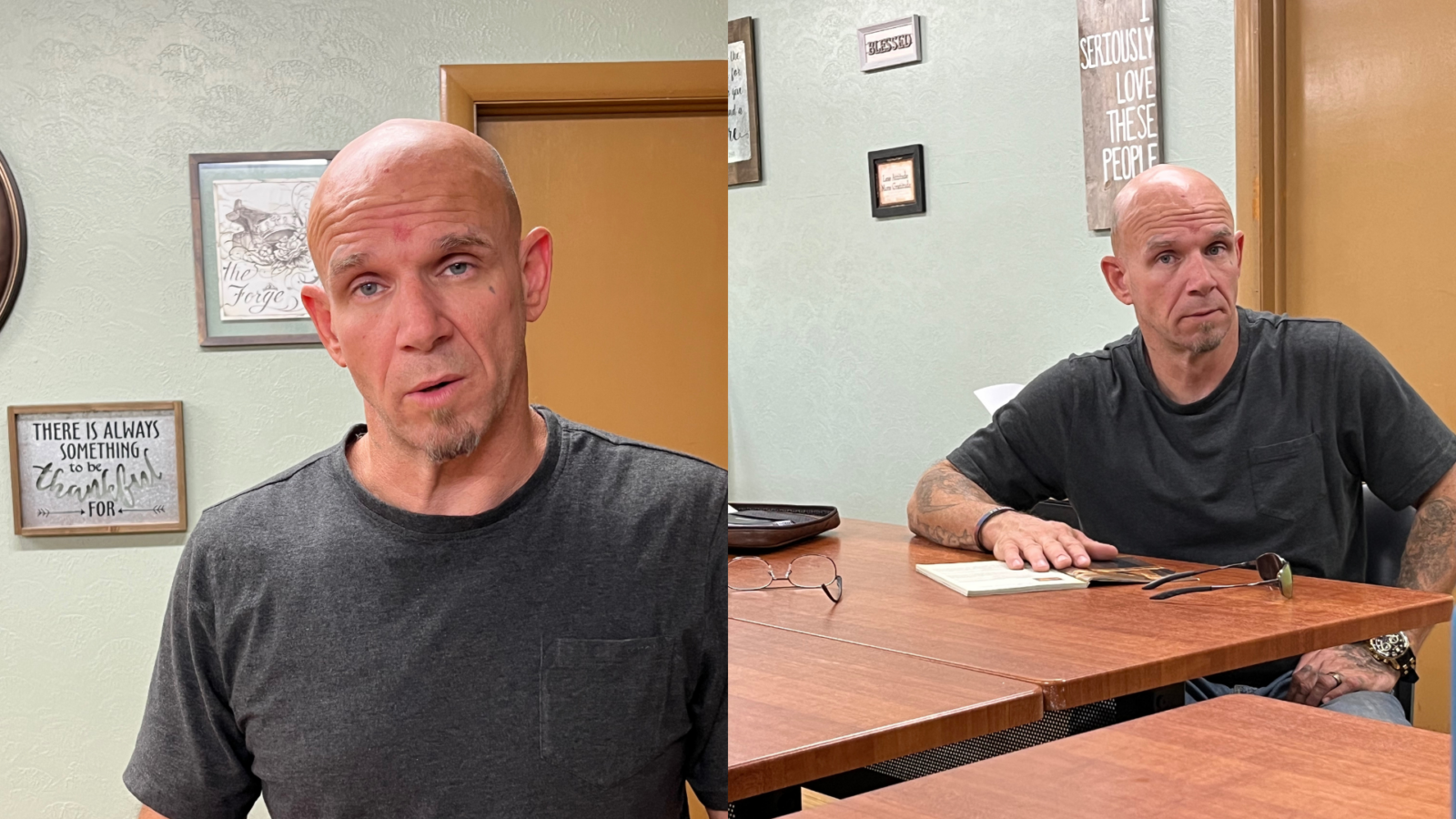

“Stay in a barbershop long enough, you’ll get a haircut.” That’s how Michael Porter described his experience after growing up in an abusive home and surrounding himself with drug addicts. He said he knifed one of them, spent six years in prison for that crime, and spent seventeen more behind bars for others. I met him last October at The Forge in Joplin, Missouri, a Christian program with daily Bible studies. He brought his 48 years of hard experience into discussions of Scripture. He also writes poems.

Here’s one verse: “Comfortable with the pain, alone is where I live/ At the bottom once again, without a lot to give/ Another tear, another year, will I ever make it home?”

Porter said he was the only boy among five sisters, an overwhelmed mom, and a Hell’s Angels stepfather who “never called me by my name, always called me Susie” (after the song, “A Boy Named Sue”). He went to a Baptist church on Sundays and a church camp during the summers and was baptized twice in the process. His most vivid memory came when he was twelve and his stepdad hit him. Porter cried. The stepdad made him put on a dress. Porter then had to stand in front of the stepdad’s pals: “That humiliated me real bad.”

One of Porter’s poems concludes with Christ saying: “Give in to the comfort I offer you/The price has been paid/The dream I give you is one that doesn’t fade.”

Porter said he ran away from home and, starting at age 13, stole cars: “I terrorized the town of Nevada, Missouri.” Time spent at the Boonville Correction Center didn’t correct him: “It was a gladiator school for people from 18 to 25 [where] I learned how to do more crimes.” Later came prison: “There you’re either white or black,” which meant Porter for self-protection joined the Aryan Brotherhood: “It was full of hatred and bred more hatred.”

Another Porter poem: “I gave my life for ransom, you chose to give yours away. I gave you simple directions but you ignored what I had to say. I sent an angel to pick you up, and you fought against his wings. Instead of reading the Bible, you chose to read Stephen King.”

In and out of prison, Porter became a soldier in drug wars. He had a son, but said “my son’s mother ended up leaving me for my best friend.” In 2016, while he was sleeping, a competitor shot him in both legs: “Getting shot opened my eyes.” He said pastor Chuck Wilson was instrumental in God opening his heart: “He came on Tuesday when I was watching Jerry Springer, and for two months I wouldn’t talk much with him. But he took a personal interest in me, and he took the time to put on an inmate’s uniform and stay in jail during lockdown, even though some of us were in for murder, some for sex crimes.”

Another Porter verse: “My love is unchanging, a promise for Eternity,/ Life everlasting if only they would turn to me.”

Porter said that during eighteen months Wilson patiently “showed me something different, taught me what forgiveness is.” Porter’s road to God has had many stops. He lived in a house for four months in which everyone else was black: “That cured me of racism.” It didn’t cure everything. Porter quit selling drugs and made some money by tattooing, but he still messed up and was arrested for driving without a license.

Porter’s poem “Why?” has God saying, “I gave you a woman to love you, but I guess she wasn’t enough. You went looking for something else, you wanted lust instead of love. You stuck a needle in your arm, just for a little high. And I’m still here: considering all you’ve done, how dare you ask me ‘why’?

The standard testimony story includes a happy ending. Six weeks after leaving The Forge, I called to see how my temporary housemates were getting along. Porter had not returned from a Thanksgiving trip home. Picked up in Fort Scott, Kansas, just across the state line, he was awaiting extradition back to Missouri and Mental Health Court.

I thought and prayed more about the poet in prison, and six weeks later asked: “Any new information?” Yes: After Porter spent a month and a half in the Vernon County Jail, the judge let him return to The Forge. Porter had told me hoped to publish his poems under the title, “Journey of a Troubled Soul.” His journey isn’t over.