If you’ve seen the TV show “Welcome Back, Kotter,” you may sense a bit of what I’m feeling now. During the 1990s I wrote a lot about homelessness, and I’m jumping back into the subject now with Fix Homelessness and the crucial subtitle of this website, “How to rebuild human lives.”

That’s human lives, not dog or cat lives. We often treat homeless humans as we do our pets, awarding them a place to sleep, a bowl with food, and no expectation of work. (Maybe they’ll entertain us.) One of my teachers during the 1990s was Marsh Ward, who for a quarter-century was clinical director at the Federal City Shelter for the Homeless in Washington, D.C.

Ward, himself a recovering alcoholic, came to Washington in 1987 to build a haven for homeless alcoholics and addicts. A half-mile from the Capitol, Ward set up his detox program to have no rules (“they’re all adults, aren’t they?”) and no pressure to prepare for a job (“nothing good available under capitalism, anyway”).

Eight years later Clean and Sober Streets, the program run by Ward and the woman he would marry, Julia Lightfoot, had definite rules and expectations: One strike (drinking, fighting, doing drugs, coming in late) and you’re out. Ward told alcoholics and addicts, “Don’t think of yourself as a victim. When you’re clean and sober you can get a job.”

What happened to change Ward’s thinking? He spoke softly to me while padding past the curtained cubicles where recent addicts slept: “Back in 1988 we believed that if you brought people in off the streets and gave them food, they’d pull themselves together and get on with their lives.” After a year he realized, “If you treat them that way, you’re killing them. You’re enabling them to stay with their disease.”

Ward also worried about the drug dealers who infested his rule-free program: “They could deal all day, then come back here for a room and hot meal, get their food stamps and welfare, then go back out and deal the next day.” Soon, to protect residents who desperately wanted to beat their addictions, Mr. Ward established rules: “Real simple: No violence, no sex. If you sit down, get too comfortable, make no progress, you’re out. Any stealing, you’re out. No alcohol, no drugs—not even legal ones, unless I’ve approved them. If you miss the curfew by one minute, you’re out.”

At first Ward tended to accept excuses for violations: “We did it sometimes just out of mercy, or sympathy because we like the guy—but it never worked out. Every time we let someone get by, he screwed up again. It’s hard to kick people out, but you also have to think of the effect on the honest people.”

One of the lines of the Lord’s Prayer—”lead me not into temptation”—explains why Ward examined every prescription his residents received: “Doctors have no sense when it comes to this group. They’ll give you stuff that will get you high. Just today I told a guy to leave. He’s on Paraflex, the muscle relaxant. We went to his locker today, got the bottle. He had taken 55 of them in the last two days. And now he’s out. That’s what we mean. He’s an addict. And if it helps you to relax and feel good, you’ll take more than is prescribed. So we play hardball.”

I interviewed many residents who welcomed the hardball approach and were ready to report rulebreakers. One resident said, “This program is saving my life. If someone messes it up, I have no hesitancy going to the office and telling them about it.” When the program began, Ward said, “there was a snitch mentality because a lot of these guys had been in prison. They wouldn’t talk. Now, they feel a part of this society.” For some, this sense carried over to the world outside Clean and Sober: They found responsible jobs and built families.

That the capitalist world was not so bad was also a revelation for Ward: “I’ve found that this society has a place for everyone who is sober and responsible, who has a skill and is willing to work. No problem.” He had seen the homeless as trapped by brick walls. He learned they were soggy cardboard. One 1990s definition of a neoconservative was “a liberal mugged by reality.” Ward’s experience was similar: “Yes, there’s racism and injustice. But, on the other hand, if I take a guy from outside, sober him up, teach him how to read, and teach him the computer, there’s a hole in the wall for that man. He goes right through.”

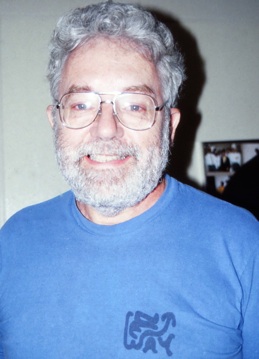

Clean and Sober Streets still exists, but I haven’t been back there and don’t know how the program has changed. I do know that Ward’s program had many successes but also many failures, and that other programs based more in grace or community can also work. I’ll be learning more about the varieties of homeless experience and will let you know what I find out. But first, a bit more about Marsh. Before coming to D.C. he worked as a psychotherapist in Minnesota and developed a droll sense of humor. He always encouraged graduates to avoid easy answers and “go deeper and then deeper again.” Born in 1934, Marsh remained Federal’s clinical director until he retired in his early 70s. He moved to a cabin in Minnesota’s north woods and died in 2016. I looked in Wikipedia to learn more biographical details about a man who changed many lives. There was no entry.